Arcadia, Indiana

Arcadia, Indiana

Couldn't load pickup availability

Arcadia, Indiana

Toby Altman

$14.95

Arcadia, Indiana is a mutant tragedy, a five act-sonnet sequence, staged in the trash-choked landscape of pastoral fantasy. It plays with narrative, labor, sexuality, and form, starting with a murder in an Indiana steel factory and ending with the Sphinx refusing all of Oedipus' solutions to her riddles. This play is a Renaissance tragedy in contemporary drag, destabilizing literary boundaries to develop a poetics of trash, in which the repressed and discarded parts of (literary) history return to strangle their point of origin.

Tragedy, Verse, Sonnets, Necropastoral

Cast: ~12M, ~3W, ~1.7kA as of 2014

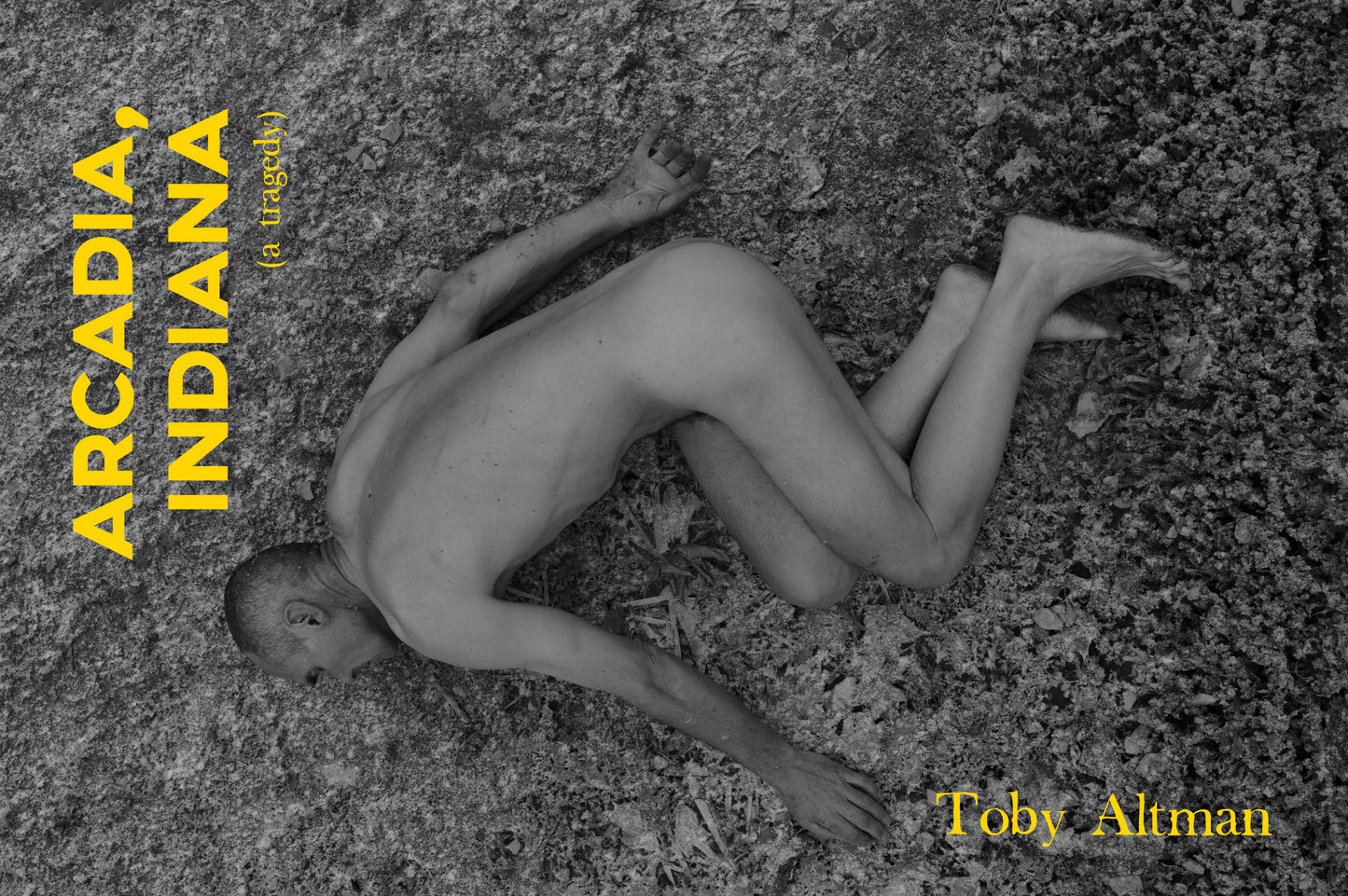

Photo by Ben Altman // Cover design by Ryan Spooner

REVIEWS

PRAISE

The factories were once the future, then they became the "rustbelt," the ruins of that future, then it turned out—with the economic meltdown and the Republican power take over—that it had been the future all along. In Toby Altman's marvelously precise, vertigonously playful and formally volatile Arcadia, Indiana, the comma of the title is the star, the true title, the space in time where the play takes place: In that space, this necropastoral play reveals that Indiana was always based on arcadia, and arcadia always had a toxic Indiana seeping through its beautiful—pre-dead, un-dead, super-dead—bodies. With this potent, maximalist work, Altman joins a language-saturated tradition of drama as poetry, or poetry as pageantry, which might also include Heiner Muller, Suzan Lori Parks, Joyelle McSweeney and Mac Wellman. At times this work reads like a crucial report from the poisoned heart of America. At other times, it reads like an ecstatic source book for how to destroy/remake theater.

—Johannes Göransson

Toby Altman's Arcadia, Indiana, a dizzying concoction of virtual theater, wordplay, carnivalesque characters, sex, parody, profound linguistic disorder, and sheer exuberance, is unlike anything else I've read. There's more sheer inventiveness in it than a reader can register. One character says, "I find I am a great many people / each one networking with the wind," and these lines characterize Altman's ability to create his remarkable panoply of speeches and verses and commentaries in this drama of the mind. In it, we encounter industrial ruin, internet-era chaos, deranged Shakespearean sonnets, innumerable allusions to other texts, and all manner of wonderfully bizarre, strangely ominous, surreal, and rococo utterances and flourishes and turns of action, setting, mood and phrase. Arcadia's manner is ceaselessly playful and startlingly dark. "Happily, language is made of uneasiness," Altman writes, and yes, this is the paradox, and Arcadia is the proof. Through its many voices, Arcadia often characterizes and comments on itself: "I want a verse that hurts the thing it says." Altman's Arcadia, like Sir Philip Sidney's, takes us on a wild ride and a rising wildness, but it's far more rambunctious than the model and will also welcome a reader who is wild. (And don't miss the Deleted Scenes, the Note on Performance and the third paragraph of the Acknowledgments!).

—Reginald Gibbons

This is the tragedy of hapless citizens in an age of cheap metal carports and expensive window frames fabricated by Arcadia Steel.

Who do not connect as they pass each other in the echoing factory.

Who are the last in their lines and have no families.

Whose amusements are stoked by resentment and pursued in rage.

Who suffer from incurable wounds.

Who indulge in savagely self-regarding Eros.

Who whip themselves toward grief.

Who find themselves already dead: "'Listen,' says Grief, 'This is the season of your unstitching.'"

Yet Altman the poet is generous in his enjoyment of all the mixtures and turnings of language to which (as offspring of the Elizabethan sonneteers, French surrealists, Samuel Beckett, and Christian Bök) he is heir.

Toby Altman is acute in capturing our era's ominous greed; he is also astute in personifying the body's organic sediments, which perform under the name "The Abominations . . . dressed in tax."

One reads him with breath held in admiration, then gasping from it.

—Mary Kinzie

Share